Here's how this works. I read a book or two and tell you about them and try not to get too long-winded, and maybe you'd like to think about reading them as well. This time, a review of

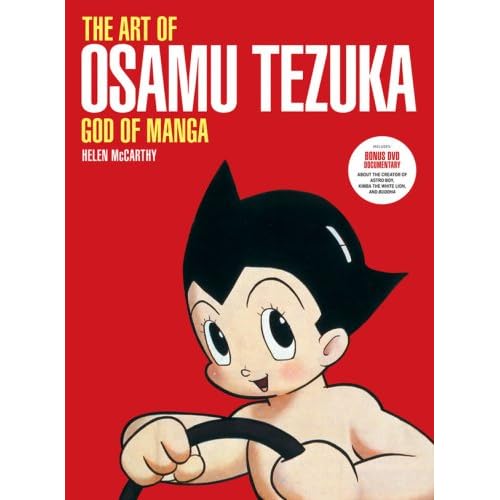

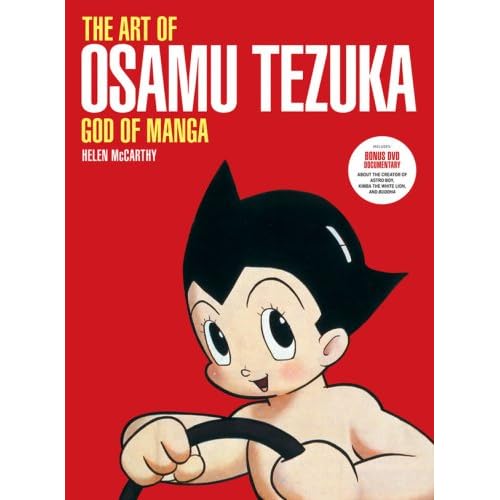

The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga (Abrams ComicArts, 2009).

So everybody reading this knows of Tezuka, right? A longtime favorite, since back in the days when I was glancing through all those lovely untranslated editions of

Vampire and

Cyborg Big X that I couldn't afford some twenty-odd years back at a shop in Doraville called Nippon Daido, he was the first Japanese comic artist to kick the medium screaming out of its four-panel gag origins and into something long-lasting and meaningful. He wasn't perfect; he was mercurial and prone to leave series uncompleted once he'd met his contractual commitment, and even within an otherwise structured series, he'd become bored and restless and prone to tilt the narrative in wild, unexpected directions. But nobody,

nobody in the medium could pull it off as well as him, and nobody designed a world where both humanity and technology could be so equally treated with love and optimism, even in works that explored our darkest possibilities. He's called the god of manga for good reason: not one American would be reading any were it not for his pioneering work.

I've had the huge pleasure of speaking with this book's author, Helen McCarthy, a few times at Anime Weekend Atlanta, and she'd agree that it's possible to go a little too overboard with the praise, and that it needs to be tempered just a little. Tezuka was a rotten businessman, and a good twenty years atop the sales charts probably left him a little complacent, and an easy target for the iconoclasts who started pushing Japanese comics in new directions in the late sixties.

Much brilliant work was still ahead of him, of course:

Black Jack, a little more than a third of which is now available in the US thanks to Vertical, and

Ayako, which they're said to be releasing next year, would be developed in reaction to a belief among younger artists that Tezuka was past his prime and relying on old glories and character designs. In the late seventies, he even had the indignity of temporarily losing the rights to his iconic

Astro Boy, requiring the creation of a substitute character, the terrifically-named Jetter Mars, for a new project.

In all, his was an amazing, restless career, the work of an artist constantly adapting to the marketplace on one hand, and forging new paths with the other. McCarthy's lovely coffeetable biography, packaged with a short documentary DVD, is the first English-language bio of one of the comic medium's most influential and important figures. Like Mark Evanier's 2008 biography of Jack Kirby - brought to you by the same publishers - it's heavily, copiously illustrated and will leave any reader desperately wanting to know more. Yet focusing, as I tend to, on Tezuka's comics and films leaves me in danger of overlooking all of the material on Tezuka's personal life. Again, McCarthy really brings a lot of fascinating material to light, with facts about his studies and his legacy, and pages of photos of the artist, in his always-present glasses and beret, always hard at work being Japan's ambassador of comics.

I must say that the

overwhelming bulk of the material in this book was completely new to me, a tidal wave of series only briefly seen mentioned in Tezuka's woefully incomplete Wikipedia listing, and much of it sounds completely fascinating. Thanks to this book, you can add quite a few more comics to my already long wish list of series that Vertical or Viz or DMP or Dark Horse or somebody needs to issue in English. Does somebody want to bring out

Barbara or

Rainbow Parakeet in the next year or two so's I can buy them?

Like the Kirby book, I do think the book is somewhat lacking for the absence of a really comprehensive Tezuka bibliography, the sort of thing that rolls on for endless detail-packed pages of minutiae and facts about exactly which issues of which anthology featured these stories in the first place, but I concede this is the sort of specialist interest not really suited to the work. All of the gorgeous art, reproduced so lovingly, and the tantalizing hints about series we've not yet seen in English just leave me hungry for more about Tezuka: more details, more facts, and

more comics. Very highly recommended.