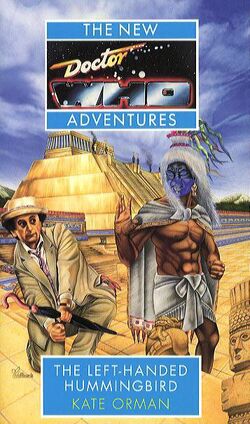

Here's how this works. I read a book or two and tell you about them and try not to get too long-winded, and maybe you'd like to think about reading them as well. This time, a review of

The Left-Handed Hummingbird (Virgin, 1994).

Doctor Who

Doctor Who's longest-serving TV producer, the late John Nathan-Turner, used to disparage his predecessors' work with a blanket warning that "the memory cheats," and the past wasn't as good as you remember it. Not the New Adventures, though, surely? Those were really good, right?

I've mentioned in my LiveJournal several times that I remain fascinated by the original TV series' final three years, because it's one of those rare times where everybody involved had far more enthusiasm and excitement than actual experience. It's the reverse of the previous Colin Baker era, where the show was a competent production of bored and lazy scriptwriting; instead, the 1987-89 seasons featured some of the most original and wonderful stories of the program's history, but only an apologist can defend the amateur-hour production that presented them. A 1978 Doctor Who episode was as lavish as anything else made for British television in 1978; a 1988 Doctor Who episode was not.

This is also mostly true of the New Adventures, a series of novels published by Virgin during the property's TV hiatus from 1991-96. Much is notable about them; apart from giving future TV wunderkind and Who savior Russell T. Davies his first professional sale, many of the concepts and continuity established in the New Adventures informed the show's 2005 resurrection. In all honesty, David Tennant's "lonely god" portrayal is just a continuation of how the seventh Doctor was depicted in these books. They were written, mostly, by novices and amateurs, fans with little more than fanfic credits behind them given the opportunity to leave a lasting mark on the Doctor Who canon.

Sadly, the writers' enthusiasm often outstripped their talents, and the books really were informed too much by the tropes of SF / Fantasy novels of the period. There is, tragically, more than one virtual reality prison in this series, and a fascination with "cyberspace" in a half-dozen different iterations that already seems hopelessly naive. Every third book seemed to feature the Doctor and some timelost figure like William Blake landing in what

seems to be a Victorian country manor, and those that didn't seemed to pit the Doctor against some nebulous Lovecraftian god/monster/entity with a stupid name from before the dawn of time or something.

The Left-Handed Hummingbird, Kate Orman's debut novel, features a villain called the Blue, for pity's sake, which is actually the psychic shockwave left behind when an Aztec warrior with low-level psychic abilities ran afoul of some space alien's radioactive detritus, destroying his body and leaving him adrift as an undying memory that has encouraged mass violence over the last 500 years. Yeah, make an action figure of

that, won't you?

I'm actually breaking one of my rules by reading this book at all. I started with the New Adventures pretty late, missing this book by about six months. As I plugged in the gaps in my collection, I encountered this author's later books in the series, which I did not enjoy, and decided this one must be skippable. Some years later, after the BBC reclaimed the publication rights, I read one of hers that was so terrible that I vowed I was done with her fiction for good. The problem seems to stem from Orman's fanfic background.

Around 1999, I read Carol Bacon-Smith's

Enterprising Women and learned about this subgenre of "hurt / comfort" fiction, terrible amateur fandom novels by daddy-issue-wracked authors wherein Captain Kirk gets impaled by something and Mister Spock comforts him, possibly, though not necessarily, just before they start smooching. Orman's books are awash with this garbage. Her later novels in the series feature alien ganglions growing out of the Doctor's shoulder, and that's before he gets impaled with an arrow, gets hypothermia, has a heart(s) attack and is confined to a wheelchair, and so on, always finding loving comfort from his companions who nurse him. It's not as though she was unaware of the trope; once, looking up a reference to make a point, I realized that the most offensive chapter in her novel

Set Piece was, in fact, entitled "Hurt / Comfort." Well, so long as she's okay with it. Her fiction depicts an endless, utterly repulsive series of sadistic, brutal, meaninglessly cruel acts, and I grew tired of wondering what the hell Doctor Who ever did to Orman to make her hate him so much. Better off not wondering, I drew a veil over her fiction.

But this one hole in my New Adventures collection was bothering the heck out of me.

In her considerable defense, Orman brought a lot more to the canon than this loathsome, over-the-top brutality. When I landed a copy of this book from paperbackswap.com last month, I knew I would get some really interesting material apart from the violence. Orman is actually responsible for one of Doctor Who's very best concepts. In

Return of the Living Dad, she established that Benny's father has lived for many years on 20th century Earth helping refugee aliens left behind after the Doctor and UNIT kicked their invading asses, which is just a lovely notion. One of these appears to be an invisible man holding a plastic spatula, but it turns out to actually just be the spatula, floating. It's an Auton spatula, left behind in 1971. That is the greatest idea ever. Her books are peppered with lovably clever bits like this.

There was only one thing I disliked about Steven Moffat's 2008 TV episode "Silence in the Library," and that's the way the Doctor could not seem to wrap his brain around the notion of meeting people, like River Song, out of sequence. Surely this happens to a time traveler with centuries of mileage all the time, right? It certainly happened in the novels far more than once, but I think that Orman did it first in her debut. It starts off wonderfully, with Cristián Alvarez, a troubled man in his fifties, meeting the Doctor, Benny and Ace for the third time, although they have not met him yet. This forces them to confront the Blue at several points throughout history, crossing Alvarez's path twice more.

However, all of the promise in Orman's concepts is overshadowed by the problems that I knew I'd find. The enemy is just a vague, ill-defined threat without any character or understandable motivation, and the gruesome violence is even worse than I feared. At various points, the Doctor bleeds from his eyeballs, bleeds from his nose and bleeds from his ears as the Blue explodes psychic bombs in his head, and he later spends three weeks being captured and tortured by some rogue lieutenant somewhere in some paranormal division of UNIT. None of this cruelty serves the plot in any way. The story would be the same with simple blackouts, and the three weeks of torture literally do not advance the plot at all, and the events are written in the most repulsively lurid manner, as though for an audience of gore fetishists. Orman once wrote a review of the TV serial "Ghost Light," a 1989 example of a tremendously good story ruined by a sloppy, barely coherent production, which suggested that she understood Doctor Who better than most, but the psychological and physical trauma that she delights in ladling out in this novel makes me question whether she ever really did.

Perhaps just as disappointing as the violence and the antagonist, there's the issue of her prose. Dan Brown has written better. You can tell it's the work of a novice, for there are characters introduced some forty pages before their first physical description. In other places, characters enter scenes by way of pronouns, three pages before we're given a name and see that it's a character that both we as readers and the other character in the scene already know. There's that fantasy-fic trope of passages that turn out to be a dream, and sequences more interested in establishing a mood of foreboding and menace without coherently defining what physically occurred. A sequence where the Doctor's old friend Professor Fitzgerald, possessed by the Blue, attacks Benny is the worst offender here, a lengthy passage that simply does not make any sense until characters explain it later, but it happens repeatedly throughout the book.

Orman certainly has her fans, and she was always rightly praised for the insightful, believable depiction of the bond between the Doctor and his companions. It's just a shame that all the good that Orman did for Doctor Who's canon had to be wrapped in these unlovable, hateful, hate-filled books. I should have left that hole in my New Adventures collection alone. Not recommended at all. Avoid.