I saw this book in my wife's to-read pile and asked "Hey! Ben Aaronovitch! You know who he is, right?"

"Never heard of him," she said. "The book sounded promising."

"He wrote a really great Doctor Who serial and another one a year later that was a lot worse. Then he wrote some of the Who novels for Virgin, each of which was better than the previous one. One of those names-to-watch, young talent of the early nineties, who sort of faded from view. I wondered what happened to him." Turns out he wrote some direct-to-CD Blake's 7 audio dramas and not much more in the way of fiction during the 2000s. In early 2011, Gollancz released Rivers of London, the first in a series of urban fantasy novels featuring a young constable, Peter Grant, who gets inducted into a secretive branch of the London police force that investigates magical doings.

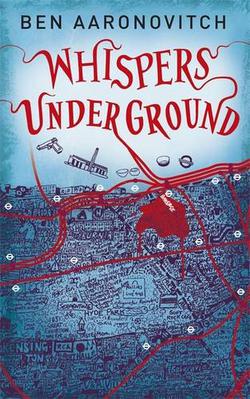

Whispers Under Ground is the third in the series and I really enjoyed it. I especially liked that while modern magic plays a big role in PC Grant's life and career and punctuates the plot and characters throughout, it is not the critical element of the actual investigation of the crime, which revolves around a doozy of a locked room mystery. The son of a New York state senator, studying art at a London college, is found dead in a station on the city's underground "Tube" Circle Line, stabbed in the back with a piece of pottery. CCTV shows him emerging from the tunnel, mortally wounded, but there's no indication of him entering the system that day. The transport police know about several service shafts and connections that the general public don't, but there's no indication that he used those, either.

The solution requires going back to the Underground's construction, and the architectural compromises made to accommodate steam engines that ran beneath the surface, and some unscrupulous vegetable sellers, and "nazareth" black markets that constantly shift location to avoid detection. It's a very fun and fascinating story, full of history and research that turn a good story into a great one. I enjoyed this a lot, and hope to read the other books in the series soon. Recommended.